Abraham Chacko is 70 years old. He has farmed cardamom in the high ranges of Idukki, Kerala for over four decades. In that time, he has witnessed three distinct eras of Indian agriculture play out on the same thirty acres of sloped forestland: the pre-chemical indigenous phase his grandfather practiced, the Green Revolution’s assault on soil fertility, and what he now calls the biological turn.

His story is not one of romance or ideology or jumping onto the latest fad. It is an honest, empirical account of failure, observation, and recalibration. As he candidly shares with us in the podcast, he was considered a “gone case nut” by his community during the transition period. He nearly gave up.

When I spoke with him, what struck me was not the success he has achieved in selling premium organic cardamom to foreign buyers at double or triple the market price. What fascinated me was his articulation of a systems framework that connects all the way from photosynthesis to soil carbon to indigenous seed varieties to Vasudeva kutumbakam (through holobiont)

It was the perfect place to do the second of my post-AI age podcast series where I sketch systems principles live in whiteboard while talking with a wide range of experts. It was also the first podcast I recorded after I rebranded Agribusiness Matters to Krishi.System

This conversation was also high-stakes: The son of a conventional cardamom farmer listened to us patiently all along and shared his challenges in convincing his parents to transition towards regenerative practices.

And that’s the reason why I keep these conversations unedited (of course, I am lazy) with all its messiness. I want to keep things raw and real. You will in fact hear one listener wondering if I would turn off the recording when we get to talk about the real challenges.Here are few fascinating systems learning principles we unearthed through the conversation.

1) Carbon as Currency

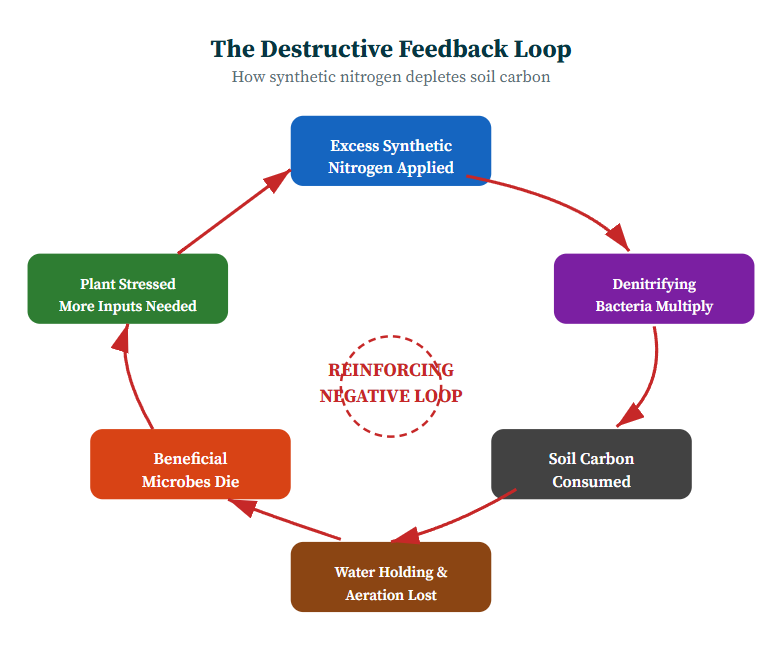

Air contains 80% nitrogen and only 0.04% carbon dioxide. Yet nature does not allow nitrogen to accumulate as an element in soil. It actively works to remove excess nitrogen through denitrifying bacteria. Carbon, however, can persist in soil—as dead microbial mass (what scientists call necromass), as organic matter, as the structural glue holding soil particles together.

Soil carbon holds eight times its weight in water. When carbon depletes, soil loses both its water-holding capacity and its aeration. Without water and air in the soil matrix, aerobic microbes cannot survive. Without microbes, plants cannot access nutrients locked in mineral form.

The system collapses.

Not from a single point of failure but from a cascade of interdependent failures.

When Chacko started applying synthetic nitrogen fertilizers in the 1980s, yields initially increased. But each year required more inputs. The soil hardened. Pests proliferated. Costs mounted. He was stuck in a reinforcing feedback loop running in the wrong direction: More nitrogen → denitrifying bacteria proliferate → soil carbon consumed → microbes die → plants stressed → more inputs needed.

The lesson took fifteen years to internalize: we were treating symptoms while accelerating the underlying disease.

2) Photosynthesis as Communication

Around 2000, Chacko encountered the work of Subhash Palekar and later the wonderful videos and writings of Christine Jones. What he learned transformed his understanding of plant biology.

The conventional model taught in agricultural colleges treats photosynthesis as a plant’s way of making food for itself. Carbon dioxide enters leaves, sunlight provides energy, glucose is produced, the plant grows.

This model is incomplete.

What scientists discovered only after 2000—through technologies like isotope tracking and confocal laser scanning microscopy—is that plants exude 30 to 40 percent of their photosynthetic products directly into the soil through their root tips. They are not leaking. They are transacting.

These root exudates are liquid carbon: dissolved sugars, organic acids, amino acids. They flow into the rhizosphere (the zone immediately surrounding roots) and feed a specific community of bacteria and fungi.

In exchange, these microbes are happy to be your unpaid interns and perform services the plant cannot do for itself: fixing atmospheric nitrogen, solubilizing phosphorus bound to soil minerals, chelating micronutrients and delivering them in plant-available forms.

Now when you supply synthetic nitrogen to a plant, you break this communication channel.

The plant no longer needs to negotiate with nitrogen-fixing bacteria. It reduces its photosynthetic exudation. Less liquid carbon flows into the soil. The microbes are fired from their job they were willing to undertake. The mycorrhizal networks that connect plants underground—what some researchers call the “wood-wide web”—collapse.

The farmer thinks she is helping the plant. She is actually severing the plant’s supply chain and immune system simultaneously.

3) Microbes as Employees

Microbes are employees of the plant. The plant manages them through exudates the way a company manages staff through compensation. Different microbes specialize in different tasks. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria handle nitrogen. Phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria handle phosphorus. Potassium mobilizers handle potassium. Each element in the periodic table that exists in soil has a corresponding microbial workforce capable of making it plant-available.

The elegance of this system is in its self-regulation. When a plant needs nitrogen, it exudes specific compounds that feed and signal nitrogen-fixing bacteria. When it needs phosphorus, it changes its exudate profile to recruit phosphorus solubilizers. The plant is not passive. It is actively farming the microbial community around its roots.

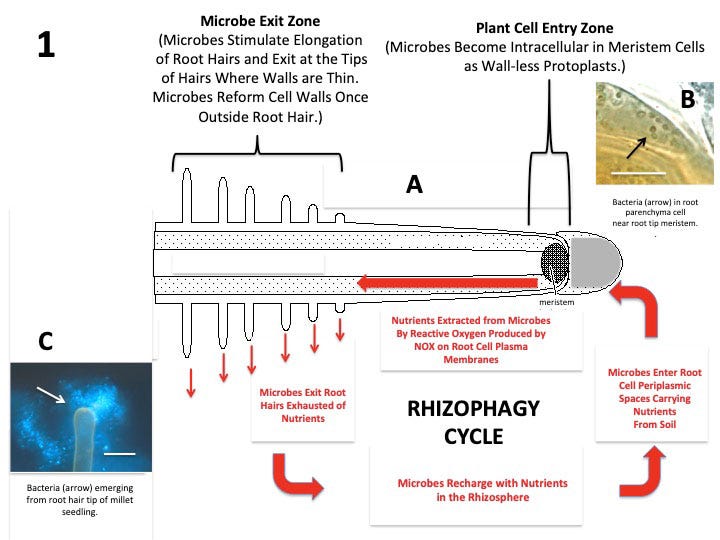

But there is a deeper layer to this relationship that science only described in 2018. James White at Rutgers University documented a process he called the rhizophagy cycle.

In this cycle, bacteria enter plant root cells at the growing tip, lose their cell walls, get partially digested by plant-produced reactive oxygen species (effectively the plant is eating part of the bacteria to extract nutrients), then surviving bacteria are expelled through root hairs back into the soil where they regain their cell walls and continue foraging for more nutrients.

The mechanism is documented across dozens of plant species. Plants are not just transacting with microbes—they are farming them, consuming them, and releasing them in cycles that may repeat every few days.

This is not alternative agriculture. This is now mainstream soil biology.

4) The Microbiome Travels in Seeds

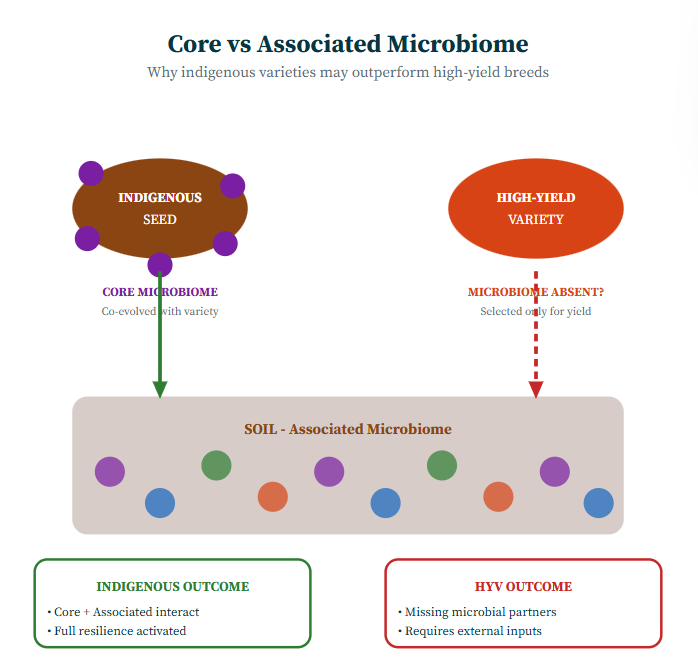

During our conversation, Chacko argued that indigenous varieties carry what he calls their “core microbiome” within the seed itself. When such seeds germinate, they arrive with a pre-adapted microbial community that has co-evolved with that variety over generations. These core microbes then interact with the “associated microbiome” already present in the soil.

High-yielding varieties that have been bred for yield alone, he suggests, may lack this core microbiome. The plant arrives in the field without its evolutionary partners. It cannot establish the microbial relationships necessary for resilience. Hence it requires external inputs to survive.

I approached this claim with skepticism. The science, however, partially supports it. Seed-transmitted endophytes are well-documented. Plants do pass microbial communities vertically through seeds. Whether the specific high-yielding cardamom varieties Chacko references lack beneficial endophytes compared to indigenous varieties would require controlled comparison studies I have not found.

But the hypothesis is testable. And it offers an explanation for why varietal selection matters beyond yield metrics: we may be inadvertently selecting against microbial partnerships when we select solely for production capacity.

6) Traditional Knowledge as Encoded Systems Understanding

Chacko aligns his planting calendar with the traditional Malayalam agricultural almanac. Cardamom planting begins on Medam Pattu (and Kanni irupaththi aaru), the day the sun is closest to Kerala on its journey between the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn. His workers—carriers of generational knowledge that predates Green Revolution—told him that planting on this date produces yield within one year. Planting two months later delays yield onset by an additional year.

He does not know why this works. He suspects it is connected with photosynthetic intensity: when the sun is closest, light energy is maximum, exudate flow is maximum, microbial establishment is optimized. The hypothesis is plausible but unverified.

Chacko treats traditional knowledge as encoded systems understanding that he is working to decode. He does not accept it uncritically. He seeks mechanisms. But he also does not dismiss it as superstition simply because the mechanism is not yet articulated.

The Economics of Transition

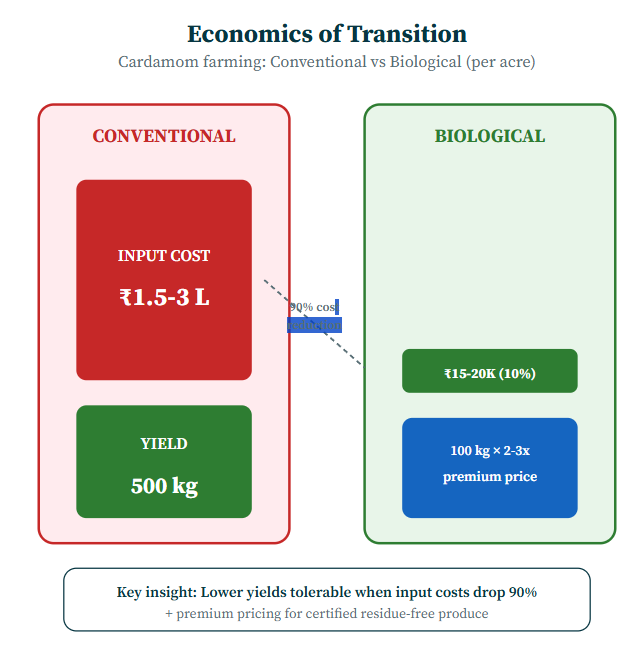

During our conversation, Chacko shared numbers that back his principles and discoveries. Chacko claims his per-acre production cost is ₹15,000 to ₹20,000. Conventional cardamom farmers in the same region spend ₹1.5 to ₹3 lakh per acre. His yields are lower: approximately 100 kg per acre versus 500 kg for intensive chemical operations.

But his cost structure is inverted. He spends perhaps 10% of what his neighbors spend. When his premium buyers pay double or triple the commodity price for certified residue-free cardamom, the math works.

Of course, we have a long way to make each of these principles emperically tamper proof. Some soil scientists argue that the “liquid carbon pathway” framework oversimplifies carbon cycling. The precise contribution of mycorrhizal fungi to soil carbon is debated. Whether seed-transmitted endophytes are agronomically significant remains an open question in many crop systems.

What Chacko has demonstrated, at minimum, that one cardamom farmer on thirty acres in the Western Ghats can transition from chemical to biological systems over a multi-decade timeframe, achieve premium market positioning, and articulate a coherent theoretical framework for his practice that aligns with emerging scientific literature.

That’s a great place to start!

Instead of asking “what inputs do I need to supply this crop,” can we ask “what relationships does this plant need to thrive?” Instead of maximizing yield per hectare, can we optimize for resilience per rupee in an age of climate chaos?

P.S. Supporting this work doesn’t have to come out of your pocket. If you read this as part of your professional development, you can use this email template to request reimbursement for your subscription.

So, what do you think?

How happy are you with today’s edition? I would love to get your candid feedback. Your feedback will be anonymous. Two questions. 1 Minute. Thanks.🙏

💗 If you like “Krishi.System”, please click on Like at the bottom and share it with your friend.