Sunday Reflections (Farmer Suicides, Amul's Moorings, Three Intermediaries of Ag)

Dear Friends,

Greetings from Hyderabad, India. Welcome to Sunday Reflections where I reflect on what I’ve written and ask myself, In doing what I am doing, what am I really doing?

<Subscriber-Only Post Trailers>

The Good, Bad and The Ugly Loans of Indian Agriculture

Indian banks are celebrating their cleanest balance sheets in over a decade. Agricultural NPAs tell a different story.

A banking expert recently assured me that farm sector stress is “within safe limits.” The data disagrees. Agriculture now accounts for 34.6% of all bad loans in the system. So how are both things true?

The answer involves a gold rush, a scheme called Kisan Credit Card bleeding at 14% delinquency, and a structural rot where crop loans are quietly paying for weddings and hospital bills instead of seeds and fertilizer.

Banks have found a way to meet their farm lending targets without actually betting on the farm. The system is secure. The farmer is not.

More in a recent subscriber-only edition of Krishi.System,

Shaktiman’s Strength and Achilles Heel

Shaktiman didn’t just become the World’s Largest Manufacturer of rotary tillers by assembling parts. They won by identifying the tiller as the foundational “atom” of Indian mechanization and obsessing over it.

From 7,500 units in 2007 to dominating >50% of the domestic market and exporting in 105 countries, their growth is a masterclass in economies of scale. But the real genius lies in their vertical integration.

They don’t just sell the printer; they own the ink. By manufacturing their own Boron steel blades—2 crore of them a year—they control the aftermarket and the product’s reputation.

Revenue grew from ₹562 crores to ₹1,690 crores. No external investors. No dilution. Pure bootstrapped scale. And yet, when I scanned their product portfolio, I found gears, chains, hydraulics, heat treatment and zero mentions of vision systems, inference chips, or autonomy.

In a world moving toward robotics, is being the best “farm implement” company enough?

More in a recent subscriber-only edition of Krishi.System

Has Amul Lost Its Moorings?

Last week, I published my piece on Amul for paid subscribers and received a lot of comments and criticism.

Given that it is Amul and I deeply care about Amul and have been deeply inspired by Verghese Kurien, I decided to publish my piece outside the paywall and address few questions that came my way!

Post-Facto: I received few fascinating comments in the wake of this piece:

Dip Patel wrote, “The cooperative model is good. But it’s losing trust. In my village, 8–9 years ago we supplied ~12,000 litres of milk per day. Today, it’s barely 3,000 litres. Unclear pricing, delayed payments, zero accountability, zero transparency, weak organisational structure, and excessive hiring — all of this eats into farmer profits. When farmers don’t understand where their milk or money goes, they walk away. And this isn’t limited to one cooperative. Even cooperative banks are facing the same trust deficit.”

Sanjaykumar Gugawad wrote, “What i can foresee is corruption may increase within organisation due non- dairy procurement/ trading products. The benchmark of 85% of revenue giving back to farmer will not work here, the bye-laws to be changed for such categories, becoz 600+ products under the belt, possibility that non-dairy business may become bigger than dairy business”

Farmer Suicides of Maharashtra

When Maharashtra Minister announced in the Legislative council that Maharashtra witnessed 781 farmer suicides in the first nine months of 2025 due to loans, crop failure and excessive rainfall, it triggered an uncomfortable question: How come the state which leads agricultural innovation is also leading the suicide list?

It set off an fascinating conversation in the Agripreneurs Community I steward.

Everyone in the room agreed on one thing: Every farmer suicide is a failure of the system, regardless of how the statistics are framed. But agreement on the tragedy didn’t mean agreement on its causes.

Obviously, The data is extremely noisy. Accidental deaths and pesticide misuse sometimes get classified as suicides. Families and officials may have incentives to fit cases into compensation frameworks. None of this negates agrarian distress. It only means that raw numbers alone cannot explain causality. The crisis is real. The numbers just don’t tell us why it persists.

The Two Maharashtras

Western Maharashtra and Konkan have reliable rainfall, irrigation infrastructure, and sugar cooperatives that created not just capital but political power. Farmers there grow grapes, sugarcane, onions, tomatoes - high financial ROI ecosystems that also shapes water priorities viciously over the long run. Many are genuinely wealthy by Indian standards.

“A typical farmer in Vidarbha would expect 225 on a 100 rs spent, does labour according to that. Rest of the time he will sit on the village katta discussing while women does rest of the work. In comparison, a farmer from western Maharashtra would expect 500 to 600 for that 100 and a farmer from Punjab/Up probably 700.” - An Agripreneur Friend from Maharashtra.

Drive east to Vidarbha or Marathwada, and the picture inverts. Rain-fed agriculture. Erratic climate. Historically neglected irrigation. Crops like cotton, soy, and wheat that offer lower margins and higher volatility. Weak political leverage translated into weak public investment, which translated into continued fragility.

This is a path-dependent trap: Poor infrastructure forces farmers into risky crops, risky crops yield low surplus, low surplus means no reinvestment, and the cycle continues. Capitalist trickle-down doesn’t work when initial conditions are broken.

Beyond the Crop Failure

One of the most important insights came from ground-level experience. Farmer suicides are rarely caused by crop failure alone. They are almost always a stacked collapse—debt, especially informal loans at 24% interest or higher; alcoholism and domestic violence; poor nutrition; climate shocks; wild animal damage; caste conflicts; social isolation; easy access to lethal means like pesticides; and zero mental health infrastructure.

This pattern isn’t uniquely Indian. Data from the UK, Australia, and France show the same thing: farming is a lonely, high-stress profession everywhere. In India, it intersects with poverty, informality, and weak safety nets—and that intersection makes it lethal.

The Silent Killer

The sharpest point of agreement was about credit. Bank credit isn’t the core problem—aggregate NPAs are manageable. The real issue is exclusion. When a district gets tagged for high NPAs, banks stop lending there. Small farmers get pushed to loan sharks. And informal debt has no restructuring, no moratorium, no forgiveness—only exponential compounding.

The suicide trigger, more often than not, is credit structure failure, not agriculture failure.

Technology Isn’t the Bottleneck

I hope Bill Gates isn’t reading this commentary on farmer suicides and is getting feverishly excited to pitch technology as a fundamental answer to smallholders’ problems.

Let’s be clear. Technology exists.

Seeds, irrigation, weather forecasting, crop insurance—all of it is available. But adoption is uneven. Risk remains individualized. Rewards are market-driven, not survival-driven. Mono-cropping for markets without buffers forces farmers to gamble with their lives.

The problem isn’t lack of innovation. It’s who bears the risk.

Whither Land Reform?

Individual smallholder farming is structurally fragile. The long-term direction—whether we like it or not—may involve land pooling, leasing models, rental income against land, and large operators running farms with scale, precision, and capital discipline. Farmers would shift from risk-bearing owners to asset-holders and skilled workers.

This is controversial, emotional, and complex. Indian agriculture may be moving—slowly and painfully—from ownership-based survival farming to enterprise-based land use.

Farmer suicides are an emergent outcome of historical neglect, uneven geography, distorted incentives, informal finance, and mental health neglect. Remove one factor, and the crisis still persists.

Reflections from Pune Agripreneurs Meetup

Pune Agripreneurs Meetup became extremely personal. We heard friends share how they fell in love with agriculture. We heard friends share how they missed the growth of their children.

We shared how we navigate our lives of entrepreneurship with family commitments.

I also goofed up with two gentlemen missing our gathering despite taking the trouble to come all the way. My sincere apologies.

This event was special with the presence of my mentor Prithwiraj N Ghorpade. We explored how our systems make it difficult to pursue our passions.

Renuka Diwan shared beautifully her journey, especially that poignant moment when it clicked to discover her passion to work with farmers. Navdeep Malhotra also shared his fascinating journey in ensuring how important it is to fulfill our svadharma besides building organizations.Deep gratitude to Sanket Kapadnis and Neeraj for joining us and sharing their journeys and dreams.

I owe another meetup to this city. I will come again.

Three Types of Intermediaries

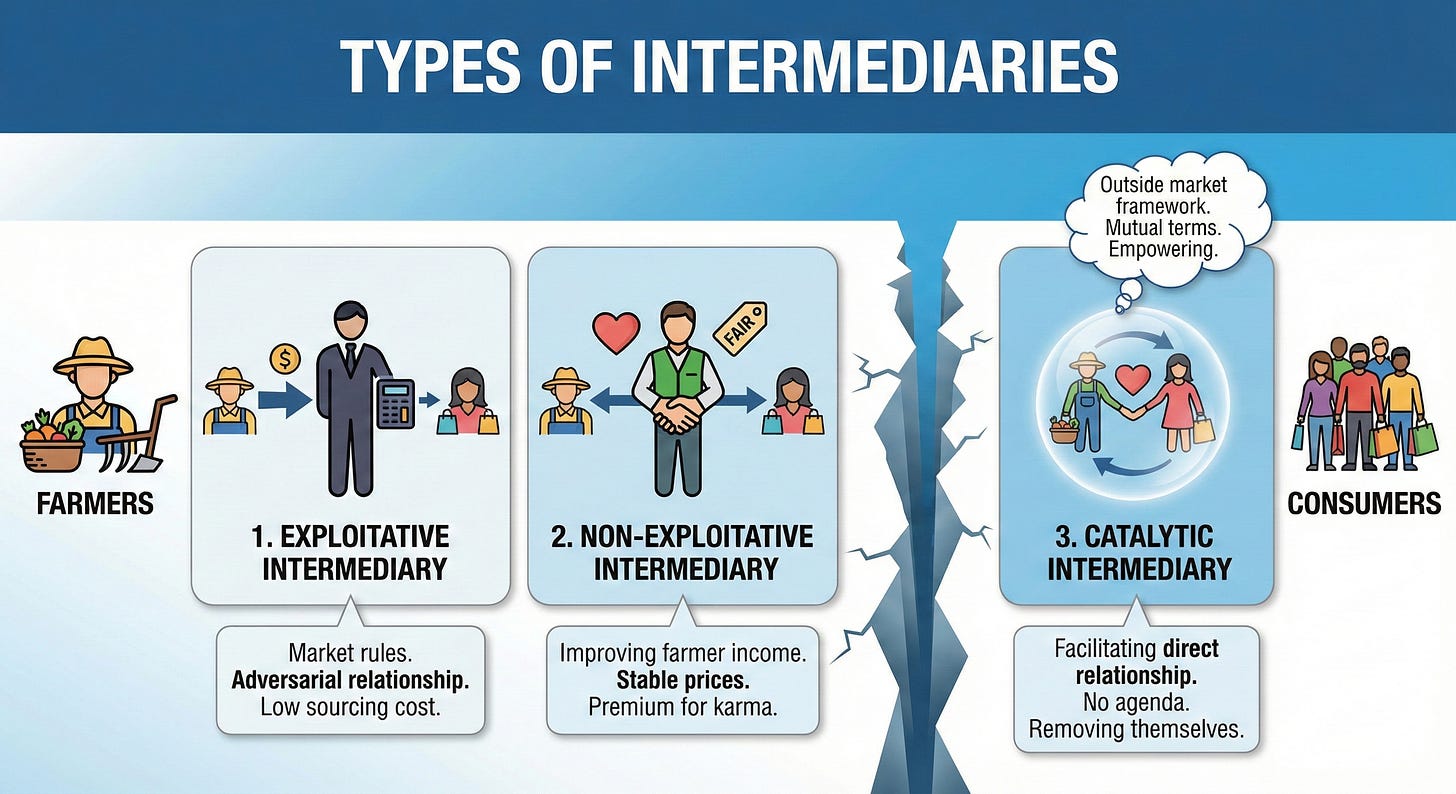

There are three kinds of intermediaries who come between farmers and consumers in smallholding agriculture contexts.

1> Exploitative Intermediary:

This is easy to understand. They play by the rules of the market. Although they share deep social relationship with farmers, in the domain of the market, they share an adversarial relationship that stems from treating farmers as "suppliers". They want to keep the cost of sourcing as low as possible. It’s a zero-sum game. The market, thanks to its vagaries, rewards them (thereby punishing farmers) and punishes them (thereby rewarding farmers). Farmers are content with this relationship as they look at the total tally of reward/punishment over a longer period of time. They are content to set the bar low and count their blessings.

2> Non-Exploitative Intermediary:

This is a niche emerging segment of intermediary players who genuinely want to improve the income of farmers through premiumisation. They track farmer incomes and set prices based on how much the farmer is making. They keep the prices fairly stable and pass on the costs to willing consumers who are willing to pay premium for the feel-good karma of treating farmers fairly. However, at the end of the day, their business lies on being an intermediary between the farmer and the consumer

3> Catalytic Intermediary:

This is a further niche segment that I met recently in Pune. Catalytic intermediaries want to bring farmers and consumers together without taking their pie. They genuinely want to empower farmers without any agenda. They see farmers as humans and aim to facilitate a relationship where farmers take care of consumers' health and consumers take care of farmers' lives.

Catalytic Intermediary exists because they exist outside the framework of markets. They understand that no matter how benevolent market might seem, it fundamentally reduces farmers into mere economic actors. They seek to address the core of the challenges faced by farmers, which goes far beyond their economic predicament. They treat farmers equally as consumers and set their relationship on mutual terms. Very few agripreneurs understand the importance and necessity of catalytic intermediary and some of them I know are striving towards removing themselves in between farmers and consumers.

Here is how the collective defines the system they have built over the past seven years:

System/Order:

1. This is not a platform for selling alone, here Organizers do not have any economic interests. This system is just a way to volunteer/contribute to the Society in order to have fair system for natural goods distributions from farmers to consumers directly.

2. This System can accommodate only a limited number of members. Hence, if needed, such a system can be duplicated at other places to accommodate more members for the same noble cause. All such Systems/Groups need to be decentralized so as to enable appropriate decision making for their own smooth functioning. Organizers can interact with each other for appropriate reasons to strengthen such Systems/Groups.

3. Everybody has a responsibility to strengthen this System/Group by their own contributions to the purpose stated above.”

Farmer’s Responsibilities and Expected Contributions

1. Farmers are expected to provide toxic-free fruits, vegetables and grains grown with the help of natural methods of farming.

2. In order to maintain sustainable farming and nutrition in food, farmers are expected to use heirloom/original seeds.

3. Farmers are expected to share their experiences and practices about sustainable farming methods and techniques.

4. Farmers are expected to provide regular updates about each crop/produce they plan to distribute on the group to maintain transparency. These updates shall include farming methods, expected produce, photos and other appropriate details related to farming.

I know of one intermediary who is building a non-profit to become a catalytic intermediary. A model of this kind cannot be built by a system-focus that inevitably moved towards scale. A model of this kind exists in scale-invariant mode and grows through human relationships.

So, what do you think?

How happy are you with today’s edition? I would love to get your candid feedback. Your feedback will be anonymous. Two questions. 1 Minute. Thanks.🙏

💗 If you like “Krishi.System”, please click on Like at the bottom and share it with your friend.