Sunday Reflections (DPI, Animal Husbandry, Ecosystem, Akshayakalpa, Living Gandhians)

Dear Friends,

Greetings from Hyderabad, India. Welcome to Sunday Reflections where I reflect on what I’ve written and ask myself, In doing what I am doing, what am I really doing?

P.S. Supporting this work doesn’t have to come out of your pocket. If you read this as part of your professional development, you can use this email template to request reimbursement for your subscription.

<Subscriber-only> Why did UKI shut down?

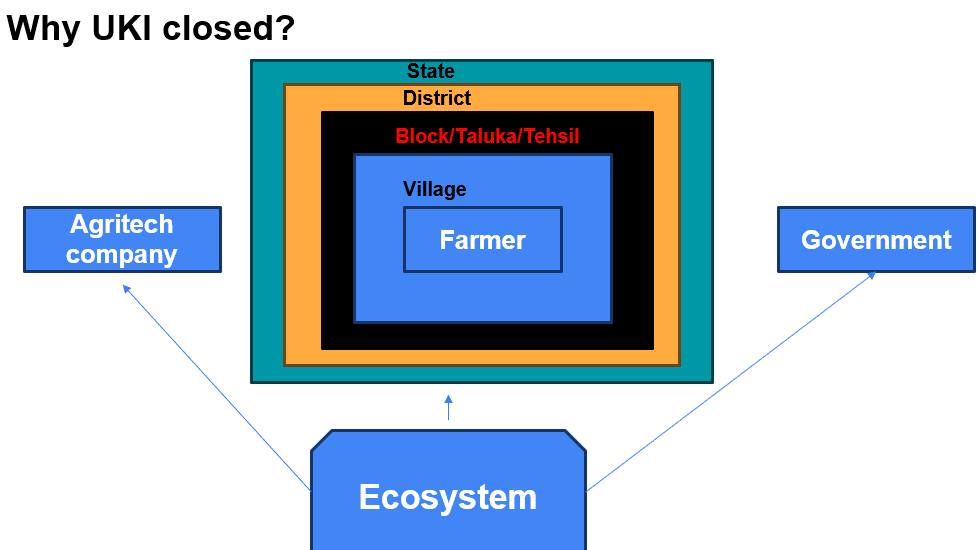

Few moons ago, I made a private presentation with an international DPI-led policy group where the main question was centered around the closure of UKI.

These are my learnings while reflecting on the death of UKI.

In smallholding contexts where farmers are deeply tied with the government ecosystem, where government is still the largest on-ground player, DPI efforts need deep government collaboration. You can’t remove them from the equation thinking private sector can create ecosystemic models. You cant afford to have arm’s length distance as well. Government has to get deeply involved from Day 1.

For DPI to be digitally sovereign for farmers, the operating atomic unit has to be at a village level. Only then, it can create structures that balance the trade-off of autonomy vs collaboration. When you start at higher levels, you end up working with aggregators who may help you scale fast, but at the cost of weak value proposition moats.

You cant place a non-profit entity at the center and expect the messiness of governance to vanish away. As many wise friends have shared with me, Government-backed navratna organisations are better suited to be the central organizing body that can house DPI structures than private corporations. Private corporations, in current political climate, do not have the risk muscle to embark on DPI led agricultural initiative.

More insights in a recent subscriber-only edition of Krishi.system.

State of Agritech (2025) with Mark Kahn and Hemendra Mathur

This conversation revealed an interesting paradox. VC is simultaneously essential for agricultural transformation yet inherently conservative in its deployment. Venture capital works as a system change lever in agriculture when three conditions align:

Pattern Recognition: The business model matches a proven playbook from another domain (consumer, B2B marketplace, fintech, or deep tech).

Unit Economics: The venture can demonstrate a path to profitability within venture time horizons, even if achieving scale requires significant capital.

Exit Visibility: There’s a credible path to liquidity through IPO or acquisition that can generate venture-scale returns.

Of the three, Exit visibility is critical to kick off the positive reinforcing loop of capital flows.

The flywheel, in its ideal state, works thus: 1) They prove that these models work, attracting more capital to similar ventures. 2) They create successful entrepreneurs and employees who start new ventures. 3) They generate returns that venture funds can recycle into new investments. 4) They shift the investor narrative from “Is Agriculture investment safe? ” to “Agriculture can generate venture returns”

Of course, the alignment here works with the select few who can crack the VC code. In the last year townhall, I wrote about how it is almost impossible to align the interests of agritech founders and investors accurately; the more the founders’ interests are aligned; the less the investors’ interests are aligned and vice-versa.

VC pattern matching is brutal for entrepreneurs. Once few patterns form, those who are aligned move forward and those who don’t slip out and die. For entrepreneurs, how do they diversify capital stack so that they don’t have to depend on VC capital and make trade offs they are not comfortable doing is the important question here.

Is it possible to align agritech founders’ interests with agritech VC’s interests? Few years down the line, we may have a clearer answer.

The complete recording and reflections spurred by the podcast recording is available for paid subscribers of Krishi.System

Stranger Things About Animal Husbandry Statistics 2025

Aaron Levenstein famously wrote that “Statistics are like bikinis. What they reveal is suggestive, but what they conceal is vital.” What does Animal Husbandry Statistics 2025 conceal about the true health of Indian Livestock sector?

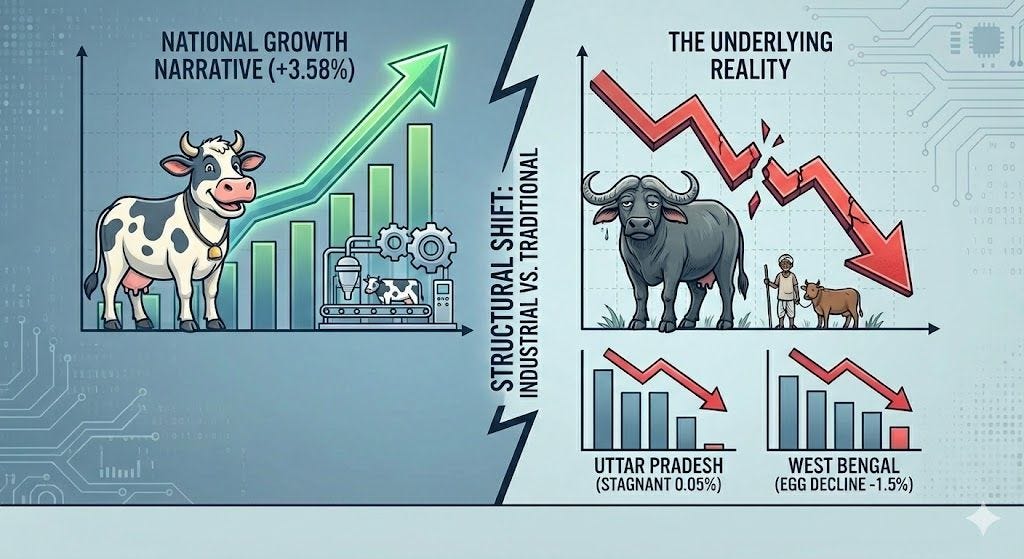

The total milk production increased by 8.57 Million Tonnes (MT) (from 239.30 MT to 247.87 MT). When I break this down at species level using 2024-25 data, exotic & Crossbred Cows contributed ~4.24 MT. Buffaloes Contributed ~2.55 MT. Indigenous and Non-Descript Cows contributed ~1.78 MT. The growth engine is now the Crossbred Cow (growing at 4.97%), while the Buffalo sector (growing at 2.45%) is dragging the average down.

Uttar Pradesh, the country’s largest producer, has effectively stopped growing (0.05% growth). In a normal year, UP would add ~1.5 MT of milk. This year, it added almost nothing. Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh massively over-performed, growing at nearly double the national rate (~6% vs 3.58%).

The strong growth in the West (Rajasthan/Gujarat) and Central India (MP) barely offset the collapse in the North (UP), resulting in the “moderate” 3.58% national average. Uttar Pradesh is the “Buffalo Capital” of India. The stagnation in UP correlates with the broader struggle in the buffalo sector.

The egg data shows stark reality on the ground. Egg production is no longer an “agricultural” activity; it is an industrial one. Commercial poultry contributed 84.49% of production (with Andhra Pradesh dominating the share as a commercial poultry hub), while backyard Poultry contributed only 15.51%.

West Bengal, the 4th largest producer, shrank by ~1.5%. This is critical because West Bengal represents “Backyard Poultry” (traditional farming). Its decline, contrasted with Andhra’s industrial boom, confirms a disconcerting fact: Small-scale poultry farming is losing ground to factory farming.

Meat production grew at 2.46%, which is sluggish compared to Eggs (4.44%) or Milk (3.58%). If Poultry (which usually grows fast) is half the basket, and the total growth is only 2.46%, it implies that Red Meat (Buffalo/Goat/Sheep) production is likely stagnant or declining. The “Meat” statistics are being propped up almost entirely by chicken. West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh are heavily reliant on Goat and Buffalo meat respectively. The two largest meat producers (West Bengal & UP) are effectively stagnant. Telangana, usually a meat powerhouse, saw its production contract by ~1%. This is a major red flag for the state’s livestock sector, likely due to disease or fodder costs.

Wool production is barely growing (2.63%) and is geographically fragile.

Rajasthan alone produces 47.85%. The second-largest producer, J&K, is growing very slowly (1.8%). A drought or disease in Rajasthan (like the heatwaves of 2024) can effectively wipe out the wool sector. We need a lot of institutional investment to revive wool production.

P.S. Special thanks to S Rajeshwaran for his incisive analysis which spurred me to probe deeper.

What I Talk About When I Talk About Ecosystem

If you’ve been following me, you would know that I use the word “ecosystem” a lot in the metaphorical sense in these spaces. But, what does it exactly mean? Sarah Frias Torres wrote a note on this and it made me ponder deeply.

“To all entrepreneurs and technical folks entering the ocean and climate solutions space: You say “ecosystem” and you don’t know what it means.

The science of Ecology studies the flow of matter and energy in the natural world. As such, Ecosystem refers to the community of living organisms and their physical environment that interact with each other in the flow of matter and energy. There are producers, consumers, and decomposers all working in sophisticated coordination, tried and tested through billions of years of evolution and natural selection.

So, in the ocean, the tiny diatoms (single-cell algae) in the phytoplankton, producers of organic matter through photosynthesis, are as important as the Blue Whale, the largest animal that has ever existed on our planet, a consumer of krill. And both, and everything in between, will be returned to nutrients thanks to the decomposers.

The problem with your start-ups and your business proposals to monetize nature is that you all want to be top predators in your “ecosystem”. You want to be Great White Sharks and Orcas, and nobody wants to be a diatom or a copepod in the plankton. Much less a fungus or a bacteria in the microbial loop completing the critical function of turning all of us back into nutrients.

Learn to use the word “ecosystem” correctly. Find your plankton and your bacteria.”

The tech world loves to use “ecosystem” as a palatable word when they want to talk about “scale” and focus on “incestuous relationships” that grow at scale.

While I work largely with the “formal” agripreneur ecosystem as a lever of change, the plankton and bacteria that recycles the innovations and converts to nutrients are the “informal” entrepreneurial ecosystem. Agriculture is perhaps the only sector in India that challenges the “Formalizing India” narrative and it’s fascinating how they act as plankton and bacteria that composts and recycles useful technologies from the formal India.

New Podcasting Project: Documenting Living Gandhians Series

Gandhians are slowly disappearing in our country and India may never produce them anymore.

“Generations to come will scarce believe that such a one as this ever in flesh and blood walked upon this earth”. Albert Einstein famously wrote this about Gandhi and I often think about this.

Had there been no documentation around the work and life of Gandhi, a few years down the line, it would have sounded like fantasy fiction.

How did this frail old man, who was politically active, wrote so much, was in touch with pan global network of friends, took time to learn tamizh and so many other languages, was interested in alternative forms of livelihood, medicine, education, agriculture and did all kinds of crazy experiments on him, and provide enough fodder and data even for his worst critics as well?

Few weeks ago, I recorded podcasts with some of the incredible last generation of Living Gandhians of the country. The first two podcasts will be published in January 2026. Who is a Living Gandhian? This is not a question of ideology. Its a question of bottom-up deep impact.

Assefa Loganathan Annachi has setup 160+ grassroots institutions with a total cap of 250+ crores, impacted 10000 villages in tamizhnadu, has pan global wide friends of assefa network and there is literally nothing on the Internet that will tell you what incredible work he has done.

Ulaganathan ayya is a living encyclopedia of rural tamizhnadu and is a storyteller of a soil that has centuries of memory compressed into acts of daily ritual, community norms, collective wisdom and dynamic enterprise.

He has watched the baby steps of SHG movement, micro credit to FPO and behemoth supply chains. There is not even a trace about Ulaganathan ayya on the Internet.

With the guidance of mentors like Ramasubramanian Oruganti, I have taken it upon myself to document their living wisdom so that when the next generation searches with deep curiosity towards Gandhi as a living tradition in this country, they will have something to connect the dots with.

I have undertaken this work in my personal expense because it is important for the commons. I want to undertake this work and document the living wisdom of Gandhians working quietly, tirelessly in the rural hinterlands of India.

Here are the living Gandhians planned as a part of the series. The first name represents the institution they have created.

1) Assefa Loganathan

2) Ulaganathan Sundaramoorthy

3) CCD Muthuvelayutham

4) Dharamitra Tarak Kate

5) Vrihi Debal Deb

6) Magan Sangralaya Vibha Gupta

7) Samanvaya Ramasubramanian Oruganti

8) CIKS Vijayalakshmi & Balu

9) Ajay Sahai

10) Indu Behen

11) Puniyamoorthy N

12) Bablu Ganguly

If you are a generous patron who could fund this important public work, do reach out.

Agripreneurs Meetup at Akshayakalpa R&D Center

Few friends from the Agripreneurs community spent an incredible weekend with Shashi Kumar (CEO, Akshayakalpa Organic) at Akshayakalpa Organic Tiptur R&D center.

Whenever I meet agripreneurs, the majority are super anxious about protecting their IP. Shashi, on the other hand are ecosystem shapers who are building structures that can pass on the lessons and knowledge from Akshayakalpa’s sixteen year journey.

This gathering was deeply special for many incredible lessons:

Akshayakalpa has pioneered an incredible extension services model that is at the heart of their stupendous growth and is now, in their next stage of evolution, building structures where extension services can be open-sourced with the larger agripreneur and FPO ecosystem.

Given how critical extension services are for the agrarian growth of our country, companies like Akshayakalpa have filled in this crucial gap that should have been ideally invested by the Government.

It was a master class for me in understanding what would a agritech company with well functioning extension services could do in the Indian agricultural context.

We met many farmers to see the contrast in how farmers who have adopted their extension services vis a vis farmers who haven’t.

We are in the plans of exploring deeper collaborations where Akshayakalpa can mentor the next generation of agripreneurs in building a sustainable and vibrant future of Indian Agriculture. Deeply grateful to Shashi Kumar for sharing so generously his valuable time with the agripreneur community, this incredible journey with such moving passion and humility and more importantly unflinching honesty.

For a long time, it was a mystery to me, having known Shashi, how him and Akshayakalpa could exist together simultaneously. I got a deeper glimpse of this mystery, with the incredible leadership team that he has built.

“Farming is muscle memory” - I will never forget this incredible lesson from Shashi in the context of agricultural education. Deeply stoked and excited to manifest many possibilities.

Here are some fascinating key glimpses from the visit, captured by fellow agripreneur Manohar:

1) “If you don’t grow your silage, don’t do dairy.”

2) “Farming has to have animals an integral part to be profitable.

3)”We are focusing on getting farmers towards 1.5 L per month/per Acre revenue. Data shows it is possible in a 5-6 years span.”

4) “9% is our budget on testing.”

5) “Extension services are key to success. But that is back breaking hardwork and costs money. Someone has to pay for it and we think it should be the consumer.”

6) We stay away from Government Schemes.

7) “We are open source. We are ready to share all our research and learnings. Cooperatives comes, gets to see. But none is implementing the model.”

8) “Amul, Nandini all have done phenomenal work. But they should now change the orbit. Deploy more resources towards extension work.”

9) Grants should be replaced with services.

10) “We pay for fellowship program. People can learn. They can start on their own or can join Akshaykalpa.”

11) “Out of the first 9 years, we were at the brink of bankruptcy 6 times. Most private players don’t see the value we create at farmer level.”

12) “You can only grow at 10-20% rate. We are fortunate to have investors who understand that.”

So, what do you think?

How happy are you with today’s edition? I would love to get your candid feedback. Your feedback will be anonymous. Two questions. 1 Minute. Thanks.🙏

💗 If you like “Krishi.System”, please click on Like at the bottom and share it with your friend.